Covid-19 – lessons for farm biosecurity?

The precautions being taken by human population due to the coronavirus pandemic have many parallels with the biosecurity measures practised by the poultry industry. Jim Bigmore, managing director of hygiene specialists Hysolv looks at some of the lessons to be learned, including misinformation, about control methods.

……… such as wearing face masks properly

……… such as wearing face masks properly.

By any standards, 2020 has been an odd year. Not judged just by sales of toilet paper and hand sanitiser, but also by how differently we treat each other. There has been a friendly wariness of family, friends and neighbours in case either they are carrying the coronavirus Covid-19, or that we might unknowingly be carrying the disease and thereby infect them. We take it for granted that we should wash our hands when we return home and wear masks when around other people.

This type of healthy paranoia should, however, be familiar to farmers in general and poultry farmers in particular, as similar measures should always have been in place on every egg or broiler unit. Wariness of contact with people outside the farm should be normal to the producer and every visitor should be regarded as a potential disease vector.

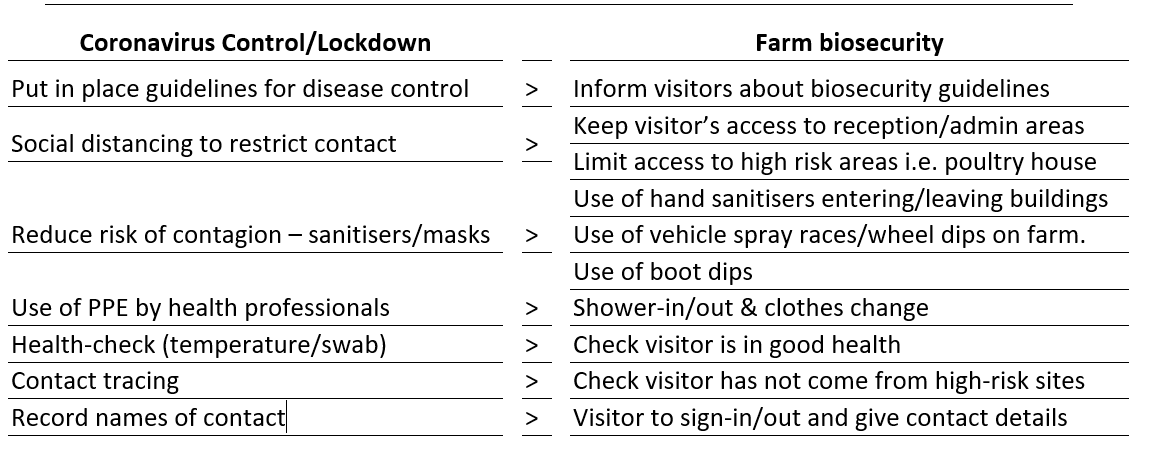

The following shows the parallels between the human health guidelines and biosecurity on the poultry farm:

As usual, the devil is in the detail. We have all seen people in supermarkets walking around with facemasks across the mouth only or, worse still, just worn under the chin.

On the farm, equipment and disinfectants need to be used properly or they won’t protect. The importance of proper disinfection cannot be over-emphasised, and it also sends an important message to staff. An empty foot dip obviously will not work but probably worse still, and less obvious, is a foot dip filled with the wrong product. It is similar to using an untested anti-malaria drug against Covid-19 or injecting disinfectant to cure a viral infection. It is certainly both ridiculous and dangerous no matter whose idea it is. Science should always lead disease control whether for humans or animals.

As with the coronavirus, finding good sources of independent scientific information is crucial! Luckily, some genuinely independent scientific comparisons of disinfectants for boot dips against the two most common zoonoses in the poultry industry – campylobacter and salmonella – have been made by the Animal and Plant Health Agency and Defra.

Campylobacter. Like many diseases, controlling transmission of “Campy” means the use of an effective boot dip and hand sanitiser. The APHA/Defra study of boot dip disinfectants2 showed that only the two chlorocresol and only one of the two iodophor disinfectants killed campylobacter in 60 seconds.

The three successful disinfectants continued to kill campylobacter in 60 seconds even after what the study described as one week’s’ simulated’ use. Peroxygen/peracetic and one of the iodophor disinfectants failed to kill Campy at all and the other disinfectants could only kill Campy after a 30-minute exposure. These are the Campy equivalent of no facemasks or one covering the mouth only.

Salmonella is another constant threat to the poultry farmer in which boot and hand sanitisation also play a key role. Once again, Defra has provided a useful comparison of the disinfectants that can be used in boot dipsii.

The disinfectants were tested in a boot dip model at Defra General Orders concentrations for 30-minute, two-hour and four-hour contact times. Under these conditions it was found that:

- Only chlorocresol, glutaral and glutaral + formaldehyde-based disinfectants kill all the salmonella in 30 minutes.

- Peroxy/peracetic and one iodophor disinfectant failed to kill the salmonella.

- All the others worked after a two-hour contact time.

As supermarkets have recognised, hand sanitation is another important way to help stop the spread of disease. A waterless hand sanitizer should have an alcohol concentration of over 70 per cent to be effective and should have been tested against common micro-organisms. For example:

Fungi – C. Albicans

Lipophilic viruses – Avian Influenza, Swine Influenza

Bacteria – S. Aureus, P. Mirabilis, E. Coli, P. Aeruginosa, E. Hirae.

This hand sanitiser should be easily accessible and fixed by the entrance to each external door of the poultry house with a clear notice inviting people to use it. Once again, the similarities with the actions taken for customers by some shops during the coronavirus pandemic are obvious.

_______________________________________________________________

i The efficacy of broiler farm boot-dip disinfectants against Campylobacter jejuni J.D. Rodgers, N.H. Kell, R.H. Davies, A.B. Vidal. Dept of Bacteriology, Animal and Plant Health Agency, Addlestone, UK.

iiIan McLaren, Andrew Wales, Mark Breslin & Robert Davies (2011) Evaluation of commonly-used farm disinfectants in wet and dry models of Salmonella farm contamination, Avian Pathology, 40:1, 33-42, DOI: 10.1080/03079457.2010.537303